"I Presume Those Are Tears Of Happiness?"

/

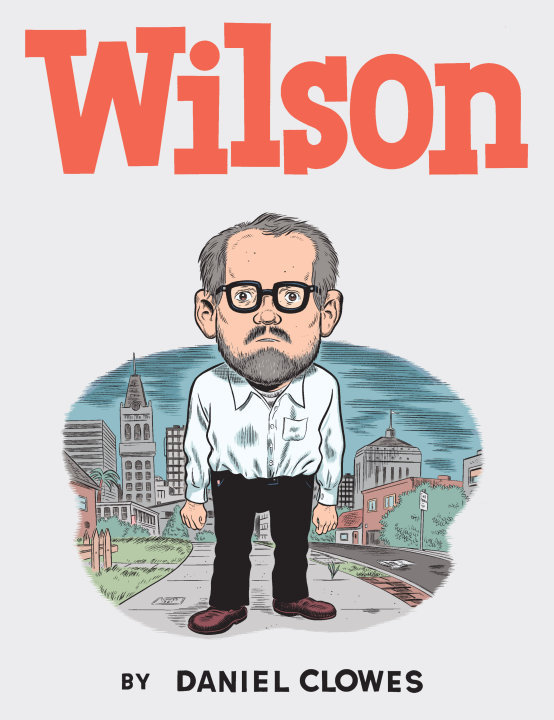

Me: “Hey, Dan Clowes has a new graphic novel coming out from Drawn & Quarterly! It’s called Wilson!”

Tiina: “Oh yeah? Is it another story about an isolated, socially awkward weirdo?”

Me: “…”

The star of Wilson is an aging, bitter malcontent, disgusted with nearly everything and everyone around him, with the exception of his beloved dog Pepper. When his father—his last living blood relative (that he knows of at this point)—dies of cancer, a suddenly despondent Wilson attempts to reconnect with his ex-wife, who informs him that the two have a now-teenaged daughter who was given up for adoption at birth. The tentatively-reconciled couple track down their daughter—a sullen creep not unlike her old man—and what begins as an uneasy family reunion almost casually morphs into a kidnapping. This is followed by incarceration, a marriage of convenience, further isolation, and a final, long-sought-after, last-page spiritual revelation that has most likely arrived way too late.

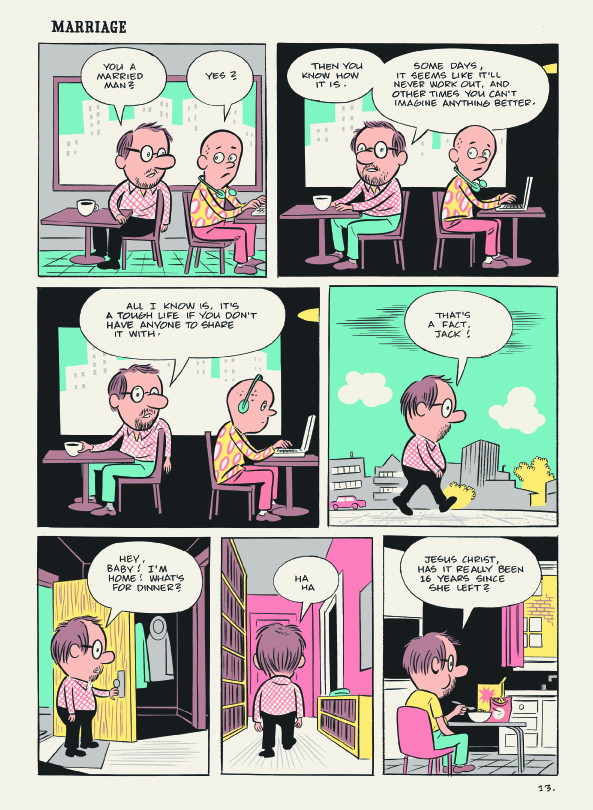

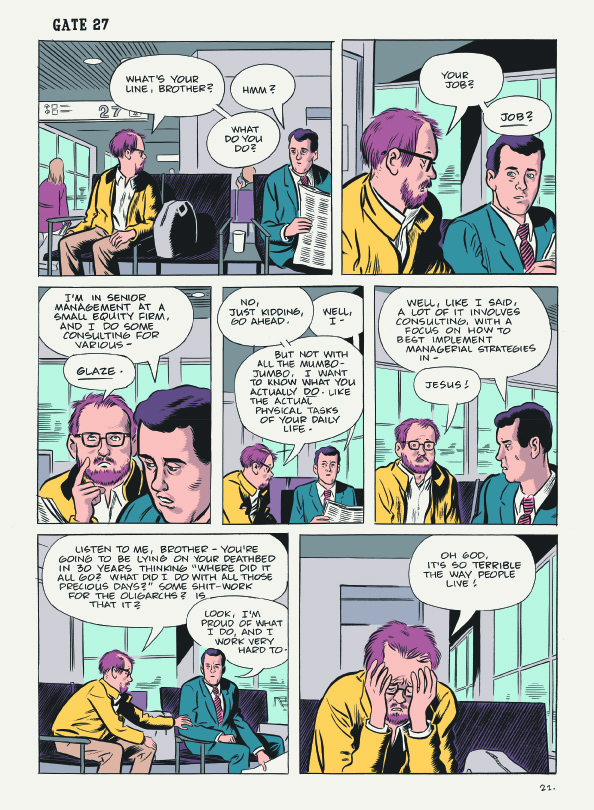

Each page of Wilson reads as an individual comic strip, rendered in its own style and colour palette, capped by a punchline that is usually either profane or heartbreaking, or both. The various cartoon styles keep things fresh as the impossible-to-like protagonist becomes more and more unpleasant. That’s not to say that Clowes doesn’t manage to evoke some sympathy for his title character—there’s a devastating (yet still kind of funny) scene near the end when the visibly aging Wilson desperately attempts to connect with his grandson via Skype; Wilson chirps happily at the kid, who is only interested in “playing the catapilla game” on the computer. Wilson is a character who, like Enid in Ghost World, willfully refuses to become a member of society, perennially disgusted by the dying bookstore market, the internet, and the proliferation of nail salons in his neighbourhood. We laugh at Wilson’s antisocial observations, while recognizing that his is a cautionary tale; if you stand outside the rest of the world long enough, you may be forever denied re-entry.

Wilson is Clowes’ first book with Canadian publisher Drawn & Quarterly, and it’s a handsome hardcover volume. However, the $21.95 price tag for 77 pages of story may be a little off-putting for some consumers. It may make you long for the days when guys like Clowes actually put out individual issues to be collected in a volume like this later, but that’s just the way the business is headed, I guess—when your periodicals only usually move a few thousand copies or so, it makes more financial sense to put the whole work out as a completed volume. Still, given the choice between several ad-ridden installments of the latest Marvel or DC crossover or an attractive, oversized hardcover that someone clearly put a few years worth of work into, I’d go with Wilson any day. The territory it covers may be familiar, but Clowes certainly knows his way around it by now.